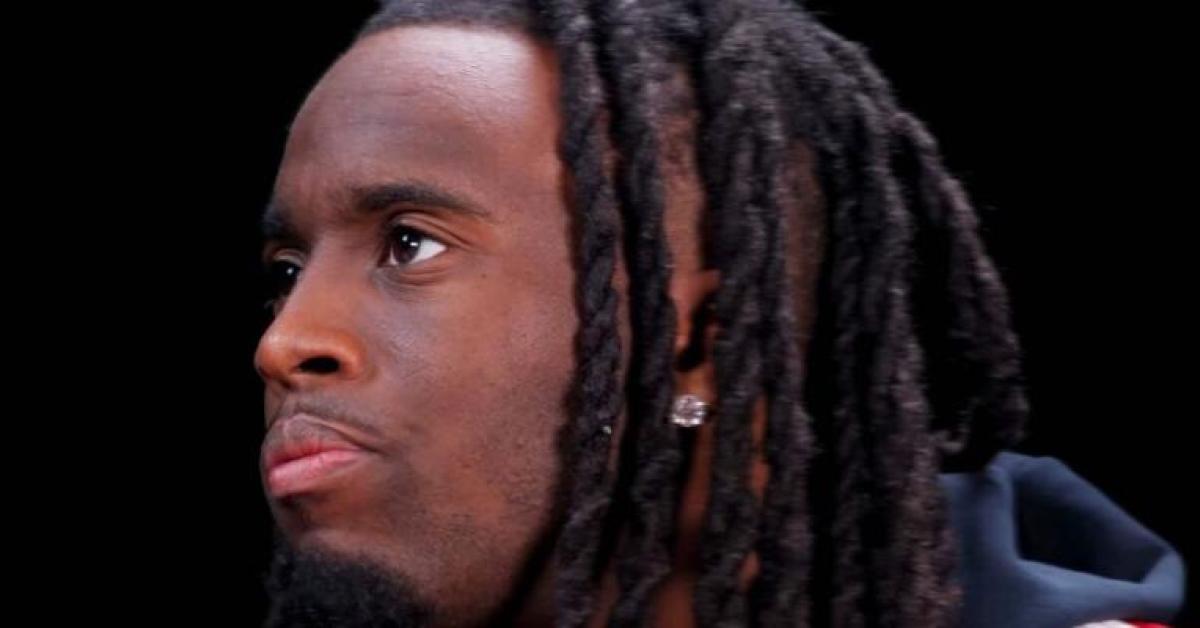

The announcement came during a marathon stream that had already broken records. Thirty days straight. Twenty-four hours a day. Kai Cenat, 22 years old, sitting in front of his camera setup doing what he does every single day—just being himself. Then the notification: One million paid Twitch subscribers.

Not followers. Not views. Not "engagement." One million people who decided that watching Kai Cenat live his life was worth paying for. Every single month. Automatically.

Do the math. At minimum, that's five million dollars monthly. Fifty percent goes to Twitch, sure, but Kai still walks away with $2.5 million. Every month. From people who chose to pay, not because an algorithm tricked them or a label forced bundles down their throats, but because they genuinely wanted to support him.

Now do this math: When's the last time a rapper sold a million albums? Not streams converted to album units. Not Spotify plays that paid fractions of pennies. Actual sales. Actual people choosing to spend actual money.

2015. That's when. Adele did it with 25. Before her? Drake, Eminem, Taylor Swift. The list gets thin fast, and rappers fall off it even faster.

Kai Cenat did in one month what most platinum rappers can't do in a career: convince a million people their product was worth paying for, directly, repeatedly, indefinitely.

That's not just a flex. That's a fundamental shift in cultural power. And if you're paying attention—really paying attention—you can feel the tectonic plates moving beneath hip-hop's feet.

The Gods We Made

There was a time when rappers were untouchable.

Not literally, of course. But the distance between artist and audience was carefully engineered, meticulously maintained, and absolutely essential to the product. You saw rappers when they wanted to be seen: on MTV, on BET, on magazine covers, in music videos where every frame was storyboarded and every image approved by managers, publicists, and label executives.

The mystique wasn't accidental. It was the whole point.

Biggie rapped about blowing up like the World Trade and we believed him because we only saw him when he was larger than life. 50 Cent showed up in a bulletproof vest and we bought it because the narrative was controlled. Jay-Z talked about moving weight and retiring in the Maybach and we couldn't fact-check it in real-time because there was no real-time.

Rappers sold aspiration. They said: "Look at my life, my cars, my chains, my women. You want this. You want to BE this."

And we did. God, we did.

Brands knew it too. In the '90s and 2000s, if you wanted to be cool, you needed a rapper. Reebok paid $50 million for Jay-Z. Sprite built entire campaigns around hip-hop. Brands didn't just want rappers in their ads—they wanted to borrow their aura, their edge, their indefinable cool.

The rapper was the ultimate cultural product: aspirational, unattainable, and therefore infinitely valuable.

The key word there is "unattainable." You couldn't touch them. You couldn't access them. You couldn't see behind the curtain.

Until suddenly, you could.

The Great Unmasking

Instagram launched in 2010. Twitter had already been around for a few years. Suddenly, the curtain didn't just have holes in it—it evaporated entirely.

At first, it seemed like a win for rappers. Direct access to fans! No media gatekeepers! They could control their own narrative!

Except they couldn't. Because the thing about 24/7 access is that it's 24/7. You can't maintain mystique when you're posting Instagram Stories from the club at 3 AM. You can't be larger than life when everyone watches you argue with your baby mama in real-time. You can't be a street legend when your arrest records, snitch paperwork, and financial troubles all trend on Twitter before breakfast.

The Shade Room became bigger than any rap blog ever was, not by breaking new artists but by breaking down existing ones. Every day, another crash-out. Every week, another rapper exposed for something—fake jewelry, rented cars, fabricated street credentials, actual crimes that destroyed their carefully crafted outlaw mystique.

6ix9ine cooperated with federal prosecutors and livestreamed his life afterward. The "stop snitching" era died in a courtroom, and everyone watched.

Tory Lanez and Megan Thee Stallion's entire legal saga played out like a reality show, except it was real, and nobody looked good.

Rappers kept beefing on social media, kept going live to address their "haters," kept responding to every slight and diss in real-time, and with every post, every tweet, every Instagram Live rant, the illusion crumbled a little more.

Fans started noticing things. Like how the "realest" rappers had the fakest interactions. How the "street" narratives fell apart under the slightest scrutiny. How the luxury lifestyle looked rented and returned by Tuesday.

The authenticity that rappers had sold as their ultimate product—their "realness," their "street cred," their "keeping it 100"—was revealed as just another costume. Another performance. And not even a good one.

Gen Z, growing up with all of this, developed what you might call immunity. They'd seen too many rappers crash out, get exposed, fall apart publicly. They'd watched the sausage being made, and it turned out the sausage was mostly filler.

The aspiration model broke. You can't look up to someone whose lowest moments are memed and whose worst decisions are documented in 4K.

Rappers had spent decades building an image of untouchable cool. Social media revealed they were just as messy, just as flawed, just as human as everyone else.

And into that vacuum stepped someone who never pretended to be anything else.

The New Parasocial Aristocracy

Kai Cenat goes live, on average, six to eight hours a day. Sometimes twelve. During Mafiathon 2, he streamed for 720 consecutive hours. An entire month.

Think about that. Think about trying to maintain a fake persona for 720 hours straight. Think about trying to be "on" for an entire month without sleep, without breaks, without the ability to cut, edit, or control the narrative.

You can't. Nobody can.

And that's precisely the point.

Streamers built their empires on a fundamentally different value proposition than rappers ever offered. Not aspiration. Companionship.

When you watch Kai Cenat, you're not watching someone you want to be. You're watching someone you feel like you know. Someone who feels like a friend. Someone whose life you're invited into, not to admire from a distance, but to participate in.

He's not selling you a fantasy life. He's sharing his actual one—the boring parts, the goofy parts, the vulnerable moments when things go wrong or get awkward or just drag on because that's what real life does.

The kids eating cereal for dinner while watching Kai play video games don't want his life. They want him in theirs. There's a crucial difference.

This is the parasocial relationship perfected. Not celebrity worship from a distance, but simulated friendship at scale. You're not a fan. You're a part of the community. You're not watching content. You're hanging out.

And when you hang out with someone six hours a day, every day, for months or years? You develop loyalty that no album rollout or music video could ever inspire.

IShowSpeed, Adin Ross, Sketch, Jynxzi—the top streamers all operate on this same model. Transparency as product. Presence as currency. Availability as the ultimate flex.

Rappers used to say "I'm so important I only appear when I want to, and you should be grateful." Streamers say "I'm here whenever you need me, and I'm not going anywhere."

In 2024, the second message won.

The Resentment Chronicles

You can feel it in the room. The tension. The unspoken hierarchy that everyone pretends doesn't exist.

A rapper walks into a streamer's setup to promote their new album. The streamer is younger, probably hasn't accomplished anything the rapper would traditionally respect—no platinum plaques, no sold-out tours, no street credibility, no co-signs from legends.

But the streamer has something the rapper desperately needs: attention. Youth attention. The kind that actually moves numbers.

So the rapper smiles. Makes jokes. Plays along with whatever bit the streamer has planned. Endures being the content, not the star.

The Kai Cenat and Wale interaction became a minor controversy for exactly this reason. Wale, a multi-platinum artist with over a decade in the industry, felt disrespected during an appearance on Kai's stream. The internet picked sides, but underneath the specific details of who said what, there was a more fundamental tension: an established artist grappling with the reality that his traditional credentials meant less than Kai's viewer count.

Plaqueboy Max—another prominent streamer—has had multiple confrontations with rappers. Lil Baby. Fivio Foreign. Others. The pattern is consistent: street-oriented rappers who've built their brands on toughness and authenticity, suddenly face-to-face with someone they'd normally dismiss as a "goofy," forced to bite their tongues because that goofy has millions of followers.

The disrespect is palpable. You can see it in body language, hear it in tone. There's a barely concealed contempt from certain rappers toward streamers—a sense that these kids haven't earned their position, haven't paid dues, haven't done anything real.

But they show up anyway. Because the math doesn't care about respect.

The appearances themselves become the problem, though. Every time a rapper swallows their pride and shows up on a streamer's platform, they prove the very thing that's destroying hip-hop's mystique: it's all just business. The "realness" is negotiable. The "street" credentials are for sale. The authenticity is a costume that comes off whenever the numbers require it.

Fans watch these interactions and see through them immediately. The rapper who claimed to be too street, too real, too authentic for the mainstream industry is now doing pratfalls for a 23-year-old streamer because that's where the audience went.

It's the final nail in the coffin of aspirational hip-hop. Not only are rappers revealed to be as manufactured as any pop star, they're revealed to be desperate. Chasing trends. Following youth culture instead of creating it.

The kings became court jesters, and everyone noticed.

The Math Doesn't Lie

Let's talk numbers, because numbers don't have egos.

A Platinum Album in 2024:

- 1 million album-equivalent units (mostly streams)

- Streams pay $0.003 to $0.005 per play

- Label takes 80-85% typically

- Producer points, feature costs, marketing recoup

- If the artist is lucky and owns some masters: $500K-$2M total

- If they don't: maybe $100K-$500K

- One-time event, sales decline immediately after release week

- Three to four year wait for the next album cycle

Kai Cenat's Mafiathon 2:

- 1 million paid subscribers (actual paying customers)

- Minimum $5/month per subscriber = $5M monthly gross

- Twitch takes 50% = $2.5M to Kai monthly

- Plus donations (easily six figures per stream)

- Plus sponsorships (seven figures for month-long integration)

- Plus merch sales

- Recurring revenue—they re-subscribe automatically

- Can repeat monthly, indefinitely

- No label. No recoup. No marketing budget to pay back.

Kai Cenat made more money in one month from subscriptions alone than most platinum albums generate for their artists, and he can do it again next month. And the month after that.

But the money is almost secondary to what it represents: loyalty. When someone subscribes, they're saying "I value this enough to pay for it, monthly, even though I don't have to."

That's not fandom. That's relationship.

Rappers used to create fans. Streamers create communities. Fans buy albums. Communities pay subscriptions.

One is a transaction. The other is a commitment.

The music industry is finally confronting what tech companies learned a decade ago: recurring revenue from loyal customers is worth infinitely more than one-time sales from casual consumers, no matter how large.

Rappers are still trying to go platinum. Streamers are building subscriber bases.

It's not even the same game anymore.

Let the Smoke Clear: The Clipse Clause

But there's a counter-narrative worth examining, because it suggests maybe—just maybe—there's another path.

Pusha T and No Malice reunited as Clipse and released Let God Sort Em Out in 2025, their first album in 15 years. They did not chase streamers. They did not manufacture viral moments. They did not try to game TikTok or court Gen Z attention.

Instead, they made calculated appearances that reinforced their brand: collaborations with Pharrell (their longtime producer), conversations with Tyler, the Creator (a fan-turned-peer), features in legacy publications that understood their context.

They focused on art, not attention. Quality, not reach. Respect within their lane, not domination across all lanes.

The album earned a Grammy nomination for Best Rap Album.

The Clipse rollout worked because they understood something crucial: hip-hop is 50 years old now. It's not a youth culture anymore. It's a mature art form with multiple sub-genres, fragmented audiences, and countless ecosystems.

You don't need everyone's attention. You just need the right attention.

For years, the industry operated under the assumption that rap belonged to the youth, and therefore rappers over 30 were finished. The past few years have proven that wrong. Kendrick Lamar is 37. J. Cole is 39. Drake is 38. The art form aged, and the artists aged with it.

What the youth owns now isn't hip-hop. It's attention itself.

When hip-hop was young, it courted attention by being edgy, controversial, dangerous. Now, in its maturity, it doesn't need to chase every trend and viral moment. It can be selective. Intentional. Focused.

The Clipse didn't need Kai Cenat because they weren't trying to be the center of youth attention. They were trying to make meaningful art for their audience—an audience that grew up with them and values substance over virality.

This is the wisdom rappers should be learning: You can't be 22 forever, and you shouldn't try. The desperation to stay relevant to teenagers makes everyone look pathetic.

Hip-hop has earned the right to multiple lanes. The question isn't "Am I hot?"—it's "Am I respected in MY lane?"

Chasing streamers for clout is the musical equivalent of a 40-year-old hanging out at the high school parking lot. It doesn't make you young. It makes you look desperate.

What Comes After Cool?

Here's the uncomfortable truth rappers don't want to admit: streamers didn't steal hip-hop's cultural power. Rappers gave it away.

Every Instagram Live rant. Every Twitter beef. Every public crash-out and desperate plea for attention. Every time a rapper broke character to reveal the insecurity underneath, they chipped away at the mystique that made them powerful in the first place.

You can't be aspirational when you're available. You can't be larger than life when you're posting from the grocery store. You can't maintain the illusion of invincibility when everyone watches you fall apart in real-time.

Rappers wanted the access that social media provided—the direct connection to fans, the ability to control their narrative—but they didn't understand that access and mystique are opposing forces. You can't have both.

Streamers understood this from the beginning. They never tried to be mystical. They built their model on the opposite: radical transparency. Constant availability. Friendship, not worship.

In an attention economy with infinite content competing for finite hours, presence beats performance. Consistency beats spectacle. Being there beats being cool.

Kai Cenat didn't have to manufacture an image because he never pretended to be anything other than himself—goofy, energetic, sometimes annoying, always present. That authenticity (or at least, the appearance of it) created trust. Trust created community. Community created recurring revenue.

Meanwhile, rappers are still trying to convince people they're cooler, richer, more dangerous, more authentic than they actually are. But everyone can see the receipts now. Everyone knows the watches are rented and the stories are exaggerated and the street credibility is managed by publicists.

The question isn't whether streamers have taken rap's place at the center of youth culture. They clearly have.

The question is whether hip-hop ever needed to be there to matter.

The View from 50

Hip-hop turned 50 in 2023. Fifty years from birth to... what exactly?

If you measure by attention, hip-hop lost. The kids are watching streams, not music videos. They're subscribing to personalities, not albums. The cultural cache that brands used to pay rappers for has migrated entirely to streamers.

But if you measure by art, by cultural impact, by the sheer depth and breadth of the form? Hip-hop won decades ago. It influenced every genre of music. It changed fashion, language, business. It created generational wealth for hundreds of artists. It gave voice to communities that had been silenced.

Maybe the real problem is that we kept measuring success by youth attention long after hip-hop outgrew being a youth movement.

Rock and roll went through this same crisis. In the '50s and '60s, it was dangerous, rebellious, the voice of youth. By the '80s, it was stadium tours and MTV. By the 2000s, it was legacy acts playing nostalgia tours.

Rock didn't die. It matured. It fragmented. It found its audiences and served them well, even if those audiences weren't 16 years old anymore.

Hip-hop is at that inflection point now. It can either chase youth attention it'll never recapture, desperately courting streamers and trying to game TikTok and manufacturing viral moments that feel increasingly inauthentic. Or it can mature gracefully, serve its audiences, focus on art over attention, and let youth culture be youth culture.

The streamers aren't the enemy. They're just the next generation doing what every generation does: creating culture that speaks to them, in the language they understand, through the medium they prefer.

Kai Cenat is bigger than rap—not because rap failed, but because rap succeeded so thoroughly that it no longer needs to be the center of everything to matter.

Hip-hop is 50 years old. It's time we stopped asking 50-year-old artists to chase 16-year-old attention spans and started letting them make the art their experience has earned them the right to make.

The youth will always move on. The art remains.

Kai Cenat has his million subscribers. Let him have them. Hip-hop has something more valuable: 50 years of proof that it changed the world.

That's not bigger than rap.

That IS rap.

Comments: 0

Add new comment